The Latvian Gambit – Part One

By Prof. Nagesh Havanur

The Latvian Gambit is one of the most exciting and fascinating openings for the Black player after the moves 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 f5!? according to experts John Elburg and Georgio Ruggeri Laderchi.

This daring defense has had a chequered past. It was the players of the Romantic School in the 16th &17th Centuries who contributed to the early theory of the Gambit. The most well-known of them was Greco and for centuries this opening was called the Greco Counter Gambit, after him.

Around the year 1900 a group of Latvian players led by K. Betinš from Riga began an independent research into the gambit and brought it up to modern standards. Over the intervening years many illustrious names have been associated with this opening – Nimzovitsch, Keres, Bronstein, and Spassky to name a few. World Champions Capablanca and Fischer have been on its receiving end.

A number of attempts have been made to prove that the gambit is unsound. However, on each occasion it has risen like a phoenix out of the ashes. The present feature offers an introduction to the opening and also presents some of my own analytical discoveries.

This system has 8 major variations, depending on White’s acceptance of the Gambit:

1. Greco Variation

2. Fraser Variation

3. Main Line

4. Leonhardt Variation

Part Two looks at the following variations:

5. 3.exf5 Variation

6. 3.d4 Variation

7. Svedenborg Variation 3.Bc4 fxe4 4.Nxe5 d5

8. Mlotkowski Variation 3.Nc3

Before we consider these variations the practical problem of dealing with irregular lines which decline the gambit should be considered. Most Latvian Gambit players feel cheated when they encounter solid moves like 3.d3. Experience, however, shows that such passive play by White only yields initiative to Black. For example, after 3…. Nc6 4.Nc3 Nf6 5.Bg5 Black plays 5..Bb4 piling pressure on e4. In such positions White should always be wary of playing exf5 as it will be countered by the thematic …d5. As for Black, he could play the restrained move …d6 as long as the White pawn is on e4. These are general guidelines, and much depends on the specific position arising out of this move order.

This brings us to the discussion of the major variations:

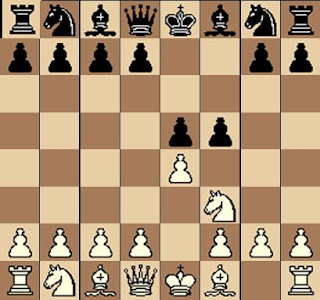

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 f5 3. Nxe5 Qe7?! This old line may well be on the way out. After 4.Qh5+ g6 5.Nxg6 Qxe4+ 6.Be2 Nf6 7.Qh3 hxg6 8.Qxh8 Qxg2 9.Rf1 Kf7

Several moves have been suggested for White: 10. Qh4, 10.d4, the sober 10. d3 and 10.b3, etc.

However, two years ago, when I played with a chess program, it came up with a new move for White 10. f4! The immediate threat is to trap the queen with Bf3. So the queen is forced to flee and reach e4, d5 or c6. Now the disadvantages of the Black position become apparent. If the queen occupies c6, it deprives the Black knight of the same square. If she occupies e4 or d5, she will be driven away by White playing N-c3 gaining valuable tempi.

Further White could play d3, not allowing the Black knight on f6 to occupy the precious square e4. It appears that the move f4 has limited the scope of White’s dark squared bishop on c1. But the state of the Black bishop on c8 is worse as he will be hemmed in by his own pawns. White can castle on the queen’s side after completing his development. Then he would launch an attack, placing his rook on g1. The most vulnerable point of Black defense is the g6-square, guarded by the king alone. In the offhand games I played with the program White invariably commenced an attack on g6 and won. In contrast Black has had a tough time ensuring that his own minor pieces would not get in each other’s way.

This brings us to the Fraser Variation which is currently undergoing a crisis.

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 f5 3.Nxe5 Nc6!? (Introduced in 1873 by the Scot G.B.Fraser) 4.Qh5+g6 5.Nxg6 Nf6

Now White has a choice between two lines: I. 6.Qh4 or II. 6.Qh3.

I. 6.Qh4

Here Black has the fantasy line 6..Rg8?! At present this line does not find favour with theory. Apparently White has two strong replies: A) 7.e5 and B) 7.Nxf8.

A) 7.e5 is an aggressive attempt to deny Black any counterplay. For example, after 7 …Nxe5 8.Nxe5 Qe7 9.Be2! Qxe5 10.d4 Qa5+ 11.Kd1! Black remains behind in development. If instead 7…Rxg6 8.exf6 Qxf6 9.Qxf6 (not 9.Qxh7?? Qe6+ 10.Be2 Rh6 The queen is trapped) 9…Qxf6 Rxf6 10.c3 d5 11.d4 White is a pawn up. Black could play 11..f4! simultaneously limiting the scope of white bishop on c1 and opening the diagonal for his own bishop on c8. But after 12. Bd3 h5 13. Nd2 it is only a matter of time for White to catch up with development and realize his material advantage.

B) 7.Nxf8 is fun.

After 7… Rg4 8.Qh6 (8.Qh3 Rxe4+ 9.Be2 Nd4 10.Nc3 Qe7 11.Nxe4 Qxe4 12.Qd3 may be even better for White) 8…Rxe4+ 9.Be2 Qe7 10.Nc3 Rxe2+ 11.Nxe2 Nxd4 12.0-0 Nxe2+ 13.Kh1 d6 14.Nxh7 Nxh7 15.Qh5+ Kf8 16. d3 Nxc1 17.Raxc1 White has the better chances according to GM Kosten who cites the game Atars-Morgado corr.1976 in his book Latvian Gambit Lives. But in the game cited above Black won! Here is the rest of the game:

17…Bd7 18. Rce1 Qf7 19.Qh6+ Kg8 20.Re3 Re8 21. Rfe1 Rxe3 22.Rxe3 Bc6 23.Rg3+ Kh8 24.Qh4 f4 25. Rh3 f3 26.Qd8+ Qg8 27.Qxg8 + Kxg8 28. gxf3 Kg7 29.Rg3+ Kf6 30.h4 Nf8 0-1

A great turnaround. While White’s resignation appears rather premature, Black deserves credit for resourceful defense and energetic counterattack. What went wrong with White? He was tempted by the exposed position of the Black king and rushed headlong into a premature attack losing the co-ordination of pieces. In fact he would have won with 22.Qxe3! Qxa2 (otherwise white plays Qe7 anyway) 23.Qe7 Bc6 24.Qd8+ Nf8 25.Qg5+ Kh8 26. Qxf5 (Fritz ) Kg8 27.Qxg5 + Kh8 28.h3! Freeing the White rook from guarding the first rank. 28…Qxb2 29. Re7 Nh7 30.Qh6 sealing the fate of the Black monarch.

The only hope for Black lies in the line 6..fxe4!? However, it is a moot point whether Black has sufficient compensation for the exchange after 7.Nxh8 d5.

II 6.Qh3 fxe4 7.Nxh8 d5

Now White has several lines like 8.Qb3, 8.Qe3, 8.Qh4 and 8.Qg3 which are analyzed in detail by Kosten. The resulting positions are random, but culminate in a symmetry of their own on occasion. A case in point is the following line: 8.Qh4 Nd4 9.Na3 Now if Black tries to recover the exchange with 9… Bxa3? and 10…Nc2+ he loses dynamism as rightly pointed out by Kosten. Instead Black should play 9…Nf5! Now if 10. Qh3 Nd4. After 11.Qc3 c5 the White queen is in a cul-de-sac.

So White has to take a draw by repetition of moves with 11.Qh4. But if White plays aggressively he may end up in an inferior position. For example, 10.Qf4 Bd6 11.Qg5 Bf8 (threatening .. Bh6) 12.Nb5 Bh6 13.Nxc7 +Ke7 14.Qxh6 Nxh6 15.Nxa8 Be6 16.d3 Nf5 17.dxe4 dxe4 18.Bd2 a5 19. Nb6 Qxb6 20.O-O-O (Fritz). White’s other knight is still trapped. Black’s minor pieces control the central squares, and he has excellent attacking chances.

White’s strongest line is 8.Qg3! not allowing Black to play ..Bg7. Even then Black is not without chances: 8.Qg3 Qe7 9.Bb5 Bg7 10.Ng6 hxg6 11.Qxg6+ Kd7 12.a4 a6 13. Bxc6+ Kxc6. According to Kosten Black has a lead in development, but it is insufficient. The game Jensen-Stummer corr.1990 continued: 14.Ra3 Be6 15.Qg3 Ng4 16.Rc3+ Bxc3 17.Qxc3+ Kd7 18.h3 Nf6 19.b4. Black has lost the initiative and his forces have been in retreat. Although he managed to draw the game in the end, the position here can hardly be considered satisfactory.

Perhaps Black’s error lay in his anxiety to secure the safety of the king and also to recover the exchange readily offered to him. In the position after 15…Ng4 Black’s minor pieces are more than a match for white rooks. Black could play the cool 16..Kb6! The monarch walks away with nonchalance to settle down at a7. If White plays carelessly with 17.h3? Black responds with 17… Be5! The White queen is trapped.

After 8.Qg3 Nd4 instead of 9.Bb5 White can play 9.Na3 with the possible continuation 9..Bd6!? 10. Qg7 Be6 11.c3 Nf5. Kosten examines a wild variation 12.Bb5+!? c6 13.Qxb7 cxb5 14.Nxb5 and claims that it offers advantage to White. But this is again a chaotic position where White’s pieces are also precariously placed.

Skeptics may point out this discussion of the Fraser Variation is inadequate if it does not take into account GM John Nunn’s supposed refutation. For the record let us see the refutation first: 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 f5 3.Nxe5 Nc6 4.d4! Qh4? 5.Nf3! Qxe4+ 6.Be2

The poor position of the queen and the lack of development render Black’s position difficult. However Black has a better defense in 4…Qf6!? as recently pointed out by John Elburg. After 5.Nc3 Bb4 Black is not without counter-chances. This line needs more practical tests in tournament play so that its real worth can be determined.

Devotees of the Fraser Variation tend to overlook the merits of the Main Line, for it covers greater territory and requires finer judgment. But the Main Line also offers opportunities for adventurous spirits.

A case in point is the following variation of the Main Line: 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 f5 3.Nxe5 Qf6 4.d4 d6 5.Nc4 fxe4 6.Nc3 Qg6

This is the key move for Black in the Main Line. The queen vacates the f6 square for the knight, guards the e4 pawn and also menaces g2 pawn. 7.f3! Nf6!? (doubtful according to theory; 7..exf3 is the usual continuation) 8.fxe4 Be7 (not 8..Nxe4 which runs into an uncomfortable pin after 9. Bd3!)

Now 9.Qd3 is too slow. Black launches the attack first as shown in the following game: 9…0-0 10.Ne3 Nc6 11.Be2 Ng4 12.Ned5 Bh4+ 13.g3 Nf2 14.Qc4 Be6 15.Rf1 Bxg3 16.hxg3 Qxg3 17.Kd2 Qg5+ 18.Ke1 Qh4 19.Ne7+ Qxe7 20.d5 Ne5 21.Qd4 c5 22.dxc6 Nxc6 23.Qe3 Nb4 24.Bd1 Nxd1 25.Rxf8+ Rxf8 26.Kxd1 Bg4+ 27.Kd2 Rf3 0-1 Thommen-Canizares 2003.

9.e5 Ng4!? is the critical test. According to Kosten this move was first played by Ionescu and popularized by Krantz.

The dangers inherent in the position may be showed by the following variation: 10.Nb5 O-O 11. Bd3 Qh5 12.Nxc7 Bh4+ 13.g3 Bxg3+ wins. Or 11.Nxc7 Qxe4+ 12.Qe2 Bh4+ 13.g3 Qxh1 14.gxh4 Nxh2 15.Nxa8 Nf3+16.Kd1 Nxd4 17.Qd3 Rxf1+ wins. So White is at a crossroads. He has a choice between: I. 10. exd6 and II. 10.Bd3.

I. 10. exd6 Bh4+!? 11.g3 0-0 12.dxc7 Nxh2!! 13.cxb8=Q Bxg3+ 14.Qxg3? (14. Kd2 Rxb8 15. Ne2 is a better defence according to Kosten) 14…Qxg3+ 15.Kd2 Nf3+ winning; Svendsen-Krantz corr. 1994-1998.

In the above line 12.dxc7? is censured as too greedy by Kosten. He recommends instead 12.gxh4. If 12…Nf2 White responds with 13.Ne5! But here Black can play 12…Qf6! 13.Qe2 Qxh4+ 14.Kd1 Nf2+ 15.Kd2 Qxd4+ 16.Ke1 Qh4! with three threats: … Nxh1+, …. Bg4, and …Rae8. Black has a winning attack. However White has a stronger defense: 13.Ne4 Qxh4+ 14.Kd2 Nf2 15.Nxf2 Qxd4+ 16.Nd3 Qxc4 17.c3 (Fritz) Black can respond with 17…Rf2+ 18.Be2 Bf5 19.Qc2 Nd7 20.b3 Rxe2+! 21.Kxe2 Qg4+ 22.Ke3 Re8+ 23.Kf2 Qh4+ wins.

II 10.Bd3 The sharpest line. There follows 10…Qh5 11.Bf4 0-0 12.Qf3 This is the critical point. In earlier games Black played 12…Nc6? and was crushed after 13.Qd5+ Kh8 14.exd6! White offers an exchange of queens and kills Black attack. Instead Black can play 12… Kh8!? now 13.0-0 runs into 13… g5 winning the pinned bishop. By a delicious irony 13.0-0-0 runs into 13…Rxf4! 14.Qxf4?? Bg5! Thus Her Majesty is lost if her Royal Consort scurries for cover to the other side.

White can play instead 13.exd6. But after 13..cxd6 he will have to come up with a better game plan to circumvent Black’s initiative. Surely, all is not lost in the Ionescu-Krantz Variation. There are also other lines like 6.Ne3 (Nimzovitsch ) and 6.Be2 (Bronstein ).

The Nimzovitsch Variation has been rendered rather innocuous on account of the following lines:

I. 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 f5 3.Nxe5 Qf6 4.d4 d6 5.Nc4 Qg6 6.Ne3 Nc6! 7.Nd5 Qf7 8.c4 Nf6 9.Nbc3 Bf5 10.Be3 0-0-0=.

The Bronstein Variation poses more dangers for Black. Even here antidotes have been found to contain White’s initiative:

II. 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 f5 3.Nxe5 Qf6 4.d4 d6 5.Nc4 Qg6 6.Be2 prevents …Qg6, Black’s anchor in this Main Line. So Black responds with a paradoxical retreat. 6…Qd8! vacating the f6 square for the knight and reserving the option of ..d5 in some lines. If White tries d5 first he will only be conceding the squares e5 and c5 for Black. Therefore White plays 7.0-0 Be7 8.f3 exf3 9.Bxf3 Nf6 10.Nc3 0-0 =

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 f5 3. Nxe5 Qf6.4.Nc4

Named after the German master Leonhardt (1877-1934) who advocated this old line. White reserves the option of playing d3 after Black has played ..fxe4 and aims at rapid development. After 4…fxe4 5.Nc3 there follows 5… Qf7! an ingenious recommendation of Gunderam, an expert on offbeat openings. Now 6.Nxe4?? loses to 6…d5 7.Ne5 Qf5 winning a knight. So White has to choose from 3 candidate moves: 6.d3, 6.d4 and 6.Ne3.

I. 6.d3 d5 7.Ne5 Qf6! 8.d4 c6 9.Be2 Bd6 10.Ng4 Bxg4 11.Bxg4 Ne7 12.0-0 0-0 =

II. 6.d4 Nf6 7.Bg5 Bb4 8.Ne5 Qe6 9.Bc4 d5 10.Bxf6 Bxc3+ 11.bxc3 gxf6 12.Qh5+ Ke7 13.Ng6+ hxg6 14.Qxh8 dxc4 15.d5 Qf5 16.0-0 Nd7 is unclear.

III. 6.Ne3 c6! 7.Nxe4 d5 8.Ng5 Qf6 9.Nf3 Bd610.d4 Ne7 11.c4 0-0=.

In this line White can play the better move 7.d3! After 7…exd3 8.Bxd3 d5 9.0-0 Bc5 10.Na4 Bd6 11.c4 Ne7 12.Nc3 0-0! (TN) 13.cxd5 cxd5 14.Nexd5 Nxd5 15.Nxd5 Nc6 16.Nc3 Be5 Black has active play for the sacrificed pawn as shown in the game Sakai –Elburg 2002.

The problem with the above variation is that Black has to worry about a knight sacrifice on d5 after 9.0-0. Kosten’s suggestion 9…Be6 10.Re1 Ne7 preventing Bf5, preparing …Nd7 and …0-0-0 may be a sounder idea.

Ωραίο άρθρο Βαγγέλη!!!Νομίζω οτι πας να τρομάξεις ψυχολογικά τους αντιπάλους σου, ενόψη και του τουρνουά!

an me auto tromaksoun… pou na doun kai to deutero meros!!! tha tromokratithoun!!!

an kai to letoniko den to ypologizo gi auto to tournoua, exei xasei tin basikitou idea to anoigma… ton aifnidiasmo.